Will Public Disclosure of Sourcing and Mfg Info Improve the US Pharma Supply Chain?

At the request of Congress, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine issued recommendations to improve the resiliency of the US pharma supply chain, including public disclosure of sourcing and manufacturing information.

The US pharma supply chain under review

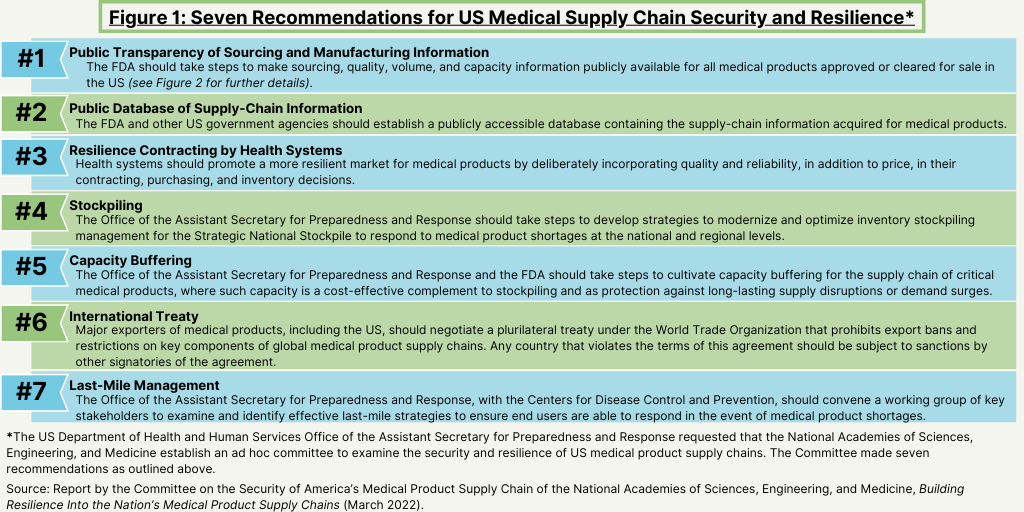

Seeking to strengthen the resilience and security of US medical product supply chains, the US Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) requested that the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine convene an expert committee to examine the root causes of medical product shortages and provide recommendations to address the most significant gaps in medical product supply-chain resilience. The resulting report, Building Resilience into the Nation’s Medical Product Supply Chains, provides seven recommendations to better enable stakeholders across US medical product supply chains to prepare and plan for, absorb, recover from, or more successfully adapt to actual or potential adverse events.

The report defines supply chain as the flow of medical products, from raw materials, to production facilities, to the “last mile” of getting products into the hands of providers and patients. It points to natural disasters, infectious disease outbreaks, geopolitical conflicts, and quality issues at manufacturing facilities as examples of events that could lead to supply-chain disruptions.

Although demand surges and supply constraints for medical products, the COVID-19 pandemic put the issue into greater focus as demand for certain products surged and manufacturers of companies developing diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines had to compete for raw materials and supplies.

Onshoring not recommended as a solution

Interestedly, unlike other policy initiatives discussed, the report does not recommend onshoring production domestically as a solution to build better resiliency in the US pharma supply chain. “The US is heavily reliant on other nations for medical products,” noted a National Academies release in highlighting the report. “However, onshoring entire medical product supply chains is costly and often not feasible. Given the global nature of supply chains, onshoring offers little protection if key components of products, such as active pharmaceutical ingredients, are sourced from other countries. Moreover, concentrating production inside the US can make supplies more vulnerable to regional disasters, such as hurricanes.” Instead, the report makes seven recommendations to improve the resilience and security of US medical product supply chains, both during public health emergencies and under normal times. The recommendations fall into four categories: awareness, mitigation, preparedness, and response. This article focuses on recommendations related to pharma supply chains rather than other medical products, such as medical devices and other medical products.

Recommendations for improving resiliency of the US pharma supply chain

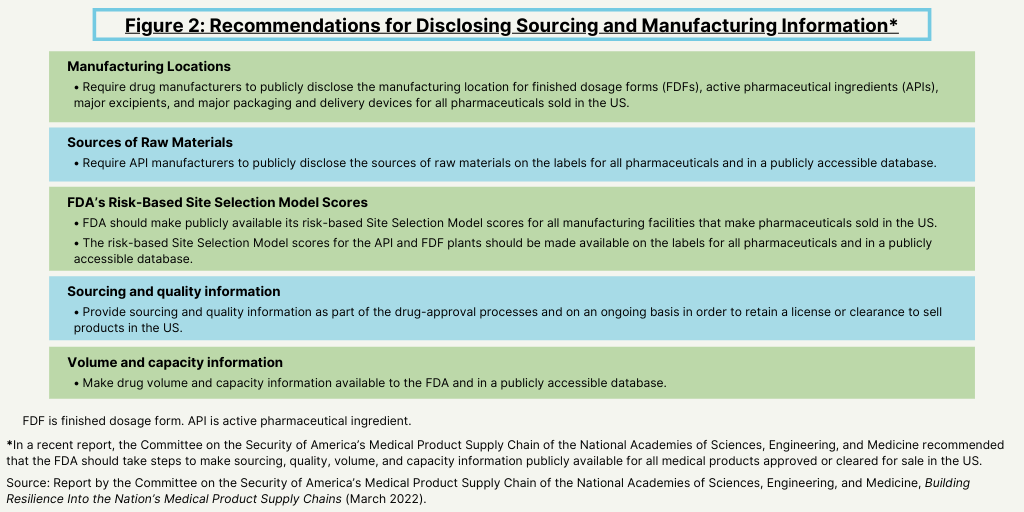

One of the key recommendations impacting bio/pharma companies, CDMOs, and suppliers is that FDA should take steps to make sourcing, quality, volume, and capacity information publicly available for all medical products approved or cleared for sale in the US, as well as related supply-chain information (see Figure 1).

The report says that enhancing awareness about medical product supply-chain risks requires transparency from manufacturers and regulators. The report recommends that the FDA should make sourcing, quality, volume, and capacity information publicly available for all medical products approved or cleared for sale in the US. It should also establish a public database to promote analyses of these data by interested parties, which the report says would produce several benefits. For example, the report says that a public database will enable health systems to make better purchasing decisions; enable policymakers to focus programs on supply-chain vulnerabilities; and provide information to the public at large to act upon data that are vital to their health, as well as place pressure on regulators and lawmakers, if appropriate.

Figure 2 details the type of information that the FDA should require and that should be made available publicly. The report recommends that drug manufacturers publicly disclose the manufacturing location for finished dosage forms (FDFs), active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), major excipients, and major packaging and delivery devices for all pharmaceuticals sold in the US. It also recommends requiring API manufacturers to publicly disclose the sources of raw materials on the labels for all pharmaceuticals and in a publicly accessible database.

In addition, the report also recommends making other information publicly available. The report recommends that the FDA should make publicly available its risk-based Site Selection Model scores for all manufacturing facilities that make pharmaceuticals sold in the US. In addition, it recommends that the risk-based Site Selection Model scores for the API and FDF plants should be made available on the labels for all pharmaceuticals and in a publicly accessible database.

The report also says that sourcing and quality information should be part of the drug-approval processes and on an ongoing basis in order to retain a license or clearance to sell products in the US. In addition, drug volume and capacity information should be available to the FDA and in a publicly accessible database.

Other recommendations

Public disclosure of sourcing, manufacturing, quality, volume, capacity, and related supply-chain information is only one area covered in the recommendations (see Figure 1 above). Other recommendations involve ways to increase mitigation, preparedness, and response to situations that cause supply-chain vulnerabilities.

Mitigation. Mitigation includes actions to help prevent a disruptive event altogether, or reduce its magnitude. The report recommends that health systems incorporate quality and reliability into their purchasing decisions, in addition to price. The report says that health systems should make suppliers pay penalties for quality issues and defects, and preferentially award contracts to suppliers that can demonstrate superior quality and reliability. It also recommends that medical product wholesalers and health systems should routinely enter into emergency purchasing agreements to guarantee that a set list of products will be delivered in the event of a disaster.

Preparedness. Preparedness actions include preventing a supply shortage from impacting patients and medical personnel. The report recommends ways the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) of the US Department of Health and Human Services can make the management of the Strategic National Stockpile more effective than it was during the COVID-19 pandemic. The report recommends that the ASPR and FDA should complement stockpiling with capacity-buffering strategies, such as setting a list of guaranteed “crisis prices” that the government would pay for certain products under specified conditions. Such measures would incentivize companies to find creative ways to meet high demand during emergencies, the report says. It also recommends that the federal government fund research on advanced manufacturing technologies that would make onshoring a reasonable strategy for some medical products.

Response. Response includes actions taken after a disruption to minimize harm from the shortage and return the supply chain to normal. The report calls for an international treaty among major exporters of medical products, including the US, under the World Trade Organization that prohibits export bans on components of critical medical products. Any country that violates the terms of this agreement would be subject to reputational, economic, or legal sanctions by other signatories. The report says that treaty negotiators could consider including provisions that facilitate information sharing, particularly during health emergencies. The report also recommends the establishment of a working group of users who represent the end of supply chains, such as clinicians, pharmacists, and public health workers. One contribution from this working group could be the collection, standardization, and dissemination of best practices, to inform last-mile management in the event of medical product shortages.