Global API Sourcing: Will Policy Impact Current Practice?

The US and the EU are continuing to advance their assessment of their supply chains for regulatory starting materials, intermediates, and APIs for essential medicines. Where do those assessments now stand, and what will be the impact on global API sourcing?

EU policy moves and APIs

In May (May 2021), the European Commission updated the European Union’s (EU) Industrial Strategy, which was first issued in March 2020, to ensure that the strategy takes into account new circumstances following the COVID-19 pandemic. The updated strategy provides a further review of information for supply-chain resilience in certain industries, including the bio/pharmaceutical industry, and specifically for the supply of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in the EU.

The updated strategy includes what the European Commission calls a “bottom-up” analysis based on EU trade data in which it identifies what it terms as “sensitive ecosystems” for which the EU is highly dependent, which includes health ecosystems, such as pharmaceutical ingredients. The updated strategy is accompanied by three Staff Working Documents, of which one is an analysis on Europe’s strategic dependencies and capacities with an in-depth review of certain industries, including pharmaceuticals.

The European Commission is evaluating its Pharmaceutical Strategy for Euroope through a structured dialogue initiative, a two-phase process steered by the European Commission. The main objective of Phase 1 is to close the knowledge gaps, by gaining a better understanding of the functioning of global pharmaceutical supply chains and identifying the precise causes and drivers of different potential vulnerabilities. Building on the evidence gathered in Phase 1, Phase 2 will result in concrete measures that will address the identified issues. The structured dialogue initiative aims to deliver results by the end of 2021 and will cover all major steps of manufacturing of medicines, in the EU and globally. Any potential measures will also comply with EU competition and World Trade Organization rules.

Inside the EU: API imports and exports

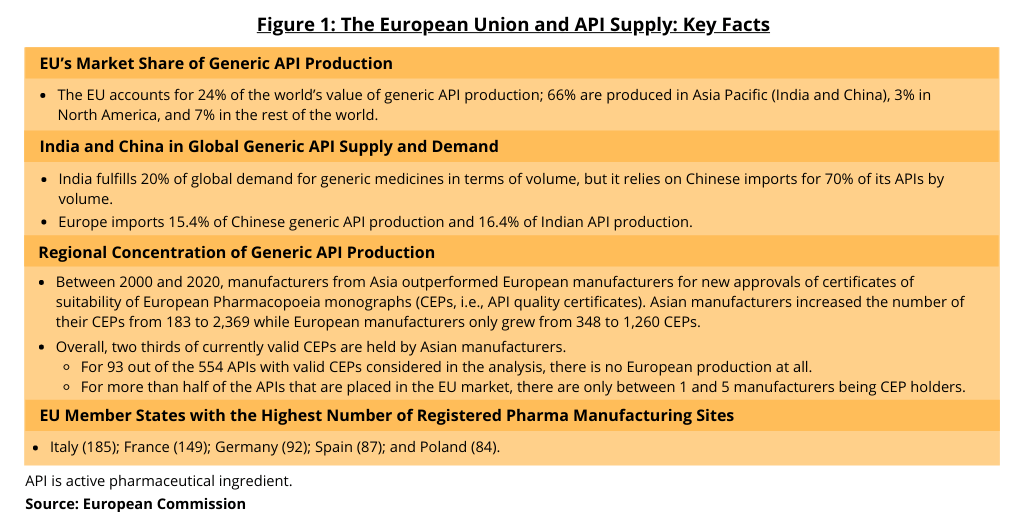

Figure 1 provides data provided by the European Commission in its assessment of the EU’s dependence on non-EU sources for APIs, in particular generic APIs. The EU’s share of global generic API production (on a value basis) is 24%; compared to 66% in Asia Pacific (India and China); 3% in North America; and 7% in the rest of the world. Additionally, European imports of APIs come from only a few sources. Eighty percent of API import volume for the EU comes from five countries: China (which accounts for 45%), India, the US, the UK, and Indonesia. Eighty percent of API import value comes from four countries: Switzerland, the US (Switzerland and US both 30%), Singapore, and China.

The assessment provides further data on the regional concentration of API supply into the EU. Between 2000 and 2020, manufacturers from Asia outperformed European manufacturers for new approvals of certificates of suitability of European Pharmacopoeia monographs (CEPs, i.e., API quality certificates). Asian manufacturers increased the number of their CEPs from 183 to 2,369 while European manufacturers only grew from 348 to 1,260 CEPs. Overall, two thirds of currently valid CEPs are held by Asian manufacturers. For 93 out of the 554 APIs with valid CEPs considered in the analysis, there is no European production at all. For more than half of the APIs that are placed in the EU market, there are only between one and five manufacturers being CEP holders (see Figure 1).

In terms of registered pharmaceutical manufacturing sites in the EU, Italy holds the most with 185, followed by France (149), Germany (92), Spain (87), and Poland (84), according to information from the European Commission. Italy followed by Spain are the largest producers of generic APIs in Europe. They both export more than 95% of their production.

Next action by the EU

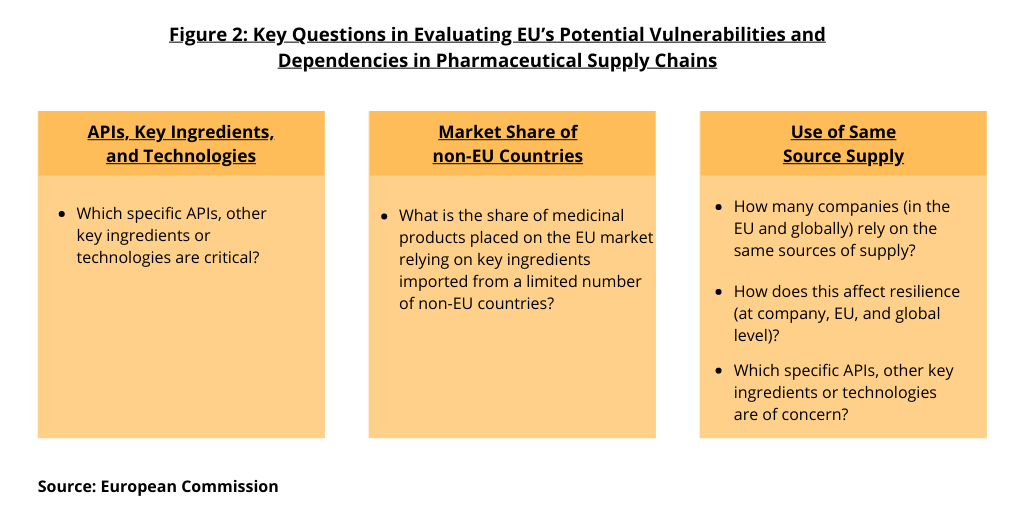

In its analysis, the European Commission says it is not sufficiently clear to what extent the EU relies on capacities in third countries (i.e., non-EU countries) in terms of processes and input required for the manufacturing of APIs. “It is essential to determine critical products, relevant from the point of view of public health, for which the EU does not have sufficient capacity to produce them,” said the Commission. Figure 2 outlines key issues that the EU is seeking to address. These include: (1) which specific APIs, other key ingredients, or technologies are critical; (2) what is the share of medicinal products placed on the EU market relying on key ingredients imported from a limited number of suppliers; (3) how many companies (in the EU and globally) rely on the same sources of supply; (4) how does this affect resilience (at company, EU, and global levels); and (5) which specific APIs, other key ingredients, or technologies are of concern.

To address these questions, the European Commission set up a structured dialogue on the security of medicines supply as announced in the Pharmaceutical Strategy for Europe in November 2020. The European Commission has initiated a structured dialogue with relevant public and private actors of the pharmaceutical supply chain. The structured dialogue will first focus on identifying the causes and drivers of potential vulnerabilities, including dependencies in the often global and complex supply chains of critical medicines, their raw materials, APIs and intermediates. At the end of July (July 2021), each work strand in the structured dialogue process (robust supply chains, critical medicinal products, vulnerabilities, and innovation) were charged with preparing a report to mark the end of operational work in Phase 1 of the process. In the second phase, after closing knowledge gaps and gaining a better understanding of the current situation, the European Commission will consider possible solutions to address issues identified.

As part of an overall approach (not industry-specific) on how the EU can reduce its dependency in strategic areas, the European Commission says that in most cases, industry itself is best placed—through its corporate policies and decisions—to improve resilience and reduce any dependencies that may lead to vulnerabilities, including through diversification of suppliers, increased use of secondary raw materials, and substitution with other input materials. “There are, however, situations where concentration of production or sourcing in only one single geographical area results in the unavailability of alternative suppliers,” said the European Commission. In areas of strategic importance, the European Commission is identifying policy measures that can support industry’s efforts to address strategic dependencies and to develop necessary strategic capacity. Such measures are generally based on a mix of actions, targeted and proportionate to ecosystems’ needs and identified risks.

US policy moves

In June (June 2021), the Biden Administration announced a series of actions and recommendations to improve supply-chain resilience in the US in several industries, including pharmaceuticals. These actions folllowed a February (February 2021) executive order issued by President Joe Biden that directed an 100-day review of certain industrial supply chains as part of an effort to identify near-term steps the Administration can take, including with Congress, to address vulnerabilities in supply chains. In addition to pharmaceuticals and ingredients, the other product areas for the 100-day supply-chain review were semiconductors, key minerals and materials, such as rare-earth metals, and advanced batteries, such as those used in electric vehicles. This 100-day review was the first step in the review of US supply chains; the Administration is also conducting a more in-depth, one-year review.

The Administration’s findings from this review, which included identifying vulnerabilities in those supply chains and recommendations to address those vulnerabilities with both industry-specific and general trade measures through executive and legislative action. The full report may be found here.

For pharmaceuticals, the Administration is recommending ways to increase domestic production of essential medicines, facilitate manufacturing innovation, and supporting other measures to facilitate trade and production in US supply chains.

Onshoring production of essential medicines, manufacturing innovation

On an immediate basis, the President directed the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), under the Defense Production Act and building on current public-private partnerships, to establish a public-private consortium for advanced manufacturing and onshoring of domestic essential medicines production. The consortium’s first task is to select 50 to 100 critical drugs, drawn from the US Food and Drug Administration’s essential medicines list, to be the focus of an enhanced onshoring effort.

The HHS will make an initial commitment of approximately $60 million from the Defense Production Act appropriation to develop novel platform technologies to increase domestic manufacturing capacity for APIs. The Administration says that greater API production domestically will help reduce reliance on global supply chains for medications that are in shortage, particularly during times of increased public health need.

Longer term, the Administration says that federal agencies should increase their funding of advanced manufacturing technologies to increase production of key pharmaceuticals and ingredients, including using both traditional manufacturing techniques and on-demand manufacturing capabilities for supportive care fluids, APIs, and finished dosage form drugs.

The Administration is also directing the HHS to develop and make recommendations to Congress on new authorities that would allow the HHS to track production by facility, track API sourcing, and require that API and finished dosage form sources be identified on labeling for all pharmaceuticals sold in the US.

Other measures

The Biden Administration also announced a series of actions to be taken across the federal government to support supply-chain resilience, workforce development, production and innovation, and strong sustainability and labor standards domestically and abroad. Highlights of some of those measures are outlined below.

Federal procurement of US-made goods. The Federal Acquisition Regulatory Council, which assists in the direction and coordination of government-wide procurement policy and regulatory activities, plans to issue a proposed rule to develop a new process for preferencing critical products that are in manufactured products or component parts to leverage the buying power of the nearly $600 billion in federal contracting to strengthen domestic supply chains for critical products.

Global Forum on Supply-Chain Resilience. The President will convene a global forum on supply-chain resilience that will bring together key government officials and private-sector stakeholders from across key US allies and partners to collectively assess vulnerabilities, develop common approaches to supply-chain challenges, and work to strengthen these supply chains.

US Supply-Chain Resilience Program. The Administration is also recommending that Congress enact a Supply Chain Resilience Program at the Department of Commerce to create a focal point within the federal government to monitor and address supply-chain challenges. It is recommending $50 billion in funding to support such a program in supply chains across a range of critical products.

Defense Production Act Action Group. The Administration is also recommending ways to deploy the Defense Production Act (DPA) to expand production capacity in critical industries through the formation of a DPA Action Group to determine how best to leverage the authorities of the DPA to strengthen supply-chain resilience by building off work done to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Improve information-sharing for risk mitigation. The Administration is also directirng the Department of Commerce to lead a coordinated effort to bring together data from across the federal government to improve the federal government’s ability to track supply and demand disruptions and facilitate information sharing between federal agencies and the private sector to more effectively identify near-term risks and vulnerabilities.

Addressing unfair trade practices. The Administration also will establish a trade strike force, led by the US Trade Representative, to propose unilateral and multilateral enforcement actions against unfair foreign trade practices that have eroded critical supply chains. The trade strike force will also identify opportunities to use trade agreements to strengthen collective approaches to supply-chain resilience with US partners and allies.

US manufacturing and exports. The Administration will also examine the ability of the US Export-Import Bank (EXIM) to use existing authorities to support US manufacturing of products. This involves the EXIM developing a proposal for Board consideration regarding whether EXIM should establish a new Domestic Financing Program that would provide financing to support the establishment and/or expansion of US manufacturing facilities and infrastructure projects in the US that would facilitate US exports.

Increasing national stockpiles. The Administration is recommending that both the Administration and Congress take actions to recapitalize and restore the National Defense Stockpile of critical minerals and materials. In the private sector, the Administration is recommending that industries that have faced shortages of critical goods should evaluate mechanisms to strengthen corporate stockpiles of select critical products to ensure greater resilience in times of disruption.

Longer-term sectorial supply-chain assessments

In addition, to the 100-day review of US supply chains, Biden’s executive order from earlier this year (2021) directs year-long reviews for six sectors, which includes the public health and biological preparedness industrial base. The other sectors are: the defense industrial base; the information and communications technology industrial base; the energy sector industrial base; the transportation industrial base; and supply chains for agricultural commodities and food production. These sectoral reviews direct federal agencies and departments to review a variety of risks to supply chains and industrial bases within 1 year of the date of the executive order issued on February 24, 2021 by which the specified heads of agencies in these six sectors, which includes pharmaceuticals, are required to submit reports to the President.

These reviews must identify critical goods and materials within supply chains, the manufacturing or other capabilities needed to produce those materials, as well as a variety of vulnerabilities created by failure to develop domestic capabilities. Federal agencies and departments are also directed to identify locations of key manufacturing and production assets, the availability of substitutes or alternative sources for critical goods, the state of workforce skills and identified gaps for all sectors, and the role of transportation systems in supporting supply chains and industrial bases. Additional details required in this assessment of US manufacturing supply chains are outlined below.

- US manufacturing capacity. The manufacturing or other needed capacities of the US, including the ability to modernize to meet future needs;

- Gaps in US capabilities. Gaps in domestic manufacturing capabilities, including nonexistent, extinct, threatened, or single-point-of-failure capabilities;

- Limited resiliency in supply chains. Supply chains with a single point of failure, single or dual suppliers, or limited resilience, especially for subcontractors;

- Location of manufacturing assets. The location of key manufacturing and production assets, with any significant risks posed by the assets’ physical location;

- Other countries involved in the supply chain. Exclusive or dominant supply of critical goods and materials and other essential goods and materials by or through nations that are, or are likely to become, unfriendly or unstable;

- Alternative sources. The availability of substitutes or alternative sources for critical goods and materials and other essential goods and materials;

- Current US workforce and gaps. Current domestic education and manufacturing workforce skills for the relevant sector and identified gaps, opportunities, and potential best practices in meeting the future workforce needs for the relevant sector;

- R&D capacity. The need for R&D capacity to sustain leadership in the development of critical goods and materials and other essential goods and materials;

- Transportation systems. The role of transportation systems in supporting existing supply chains and risks associated with those transportation systems; and

- Climate-change risk. The risks posed by climate change to the availability, production, or transportation of critical goods and materials and other essential goods and materials.

In addition, the supply-chain assessments also are to include whether there are possible avenues for international engagement with US allies and partners for the critical goods and materials and other essential goods and materials identified in the review of the given sector’s supply chain. In addition, the assessment should identify the primary causes of risks for any aspect of the relevant industrial base and supply chains assessed as vulnerable. The assessment should include a prioritization of the critical goods and materials and other essential goods and materials, including digital products for the purpose of identifying options and policy recommendations. The prioritization is to be based on statutory or regulatory requirements, importance to national security, emergency preparedness, and US policy.

Agencies are directed to make specific policy recommendations to address risks as well as proposals for new research and development (R&D) activities. The executive order specifies that the policy recommendations for ensuring a resilient supply chain for a given sector should evaluate the following:

- Reshoring. Sustainably reshoring supply chains and developing domestic supplies;

- Alternative supply chains. Cooperating with allies and partners to identify alternative supply chains;

- Redundancy. Building redundancy into domestic supply chains;

- Stockpiles. Ensuring and enlarging stockpiles;

- Workforce. Developing workforce capabilities;

- Financing. Enhancing access to financing;

- R&D capacity. Expanding R&D to broaden supply chains;

- Digital-products risks. Addressing risks due to vulnerabilities in digital products relied on by supply chains;

- Climate-change risks. Addressing risks posed by climate change, and any other recommendations;

- US government support and policy. Any executive, legislative, regulatory, policy changes and any other actions needed to strengthen capabilities; and

- Other US government efforts. Proposals for improving the US government-wide effort to strengthen supply chains.

Going forward, after this initial 1-year view of supply chains, the executive order specifies that the US government also plans to conduct regular, ongoing reviews of supply-chain resilience, including a quadrennial review process.