Re-inventing US Pharma Mfg and Supply Chains

The Association for Accessible Medicines, which represents generic-drug and biosimilar manufacturers in the US, put forth a blueprint to facilitate a repatriation of pharma manufacturing to the US. What does the plan recommend?

A plan for re-inventing the US pharma supply chains

One consequence of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic from industry as a whole is a re-thinking of global supply chains and the need to increase domestic manufacturing to assure supply and mitigate potential product shortages. This conversation is also occurring in the pharmaceutical industry. Late last month (April 30. 2020), the Association for Accessible Medicines (AAM), which represents generic-drug and biosimilar companies and manufacturers in the US, released a report, A Blueprint for Enhancing the Security of the US Pharmaceutical Supply Chain, a six-element framework that lays out actions that the federal government could take to ensure a consistent supply of critical pharmaceuticals. The blueprint builds upon the existing generic pharmaceutical supply chain in the US, which produces more than 61 billion doses annually in nearly 150 manufacturing facilities across the US, according to information from the AAM.

“The generic pharmaceutical supply chain, which provides 90% of prescriptions filled in the United States, is demonstrating remarkable resiliency during the COVID-19 crisis, and AAM and its member companies are committed to applying the lessons that we have learned to make the supply chain stronger and more secure,” said Jeffrey K. Francer, AAM’s Interim CEO and General Counsel, in an April 30, 2020 statement. “The blueprint contains specific steps that Congress and the Executive Branch could take to create the capacity to manufacture critical medicines in the United States and allied countries, leading to increased national security, a reduction of dependence on any one country for key pharmaceuticals or their components, and an expanded employment base.”

A proposal for increasing US-based manufacturing for high-priority medicines

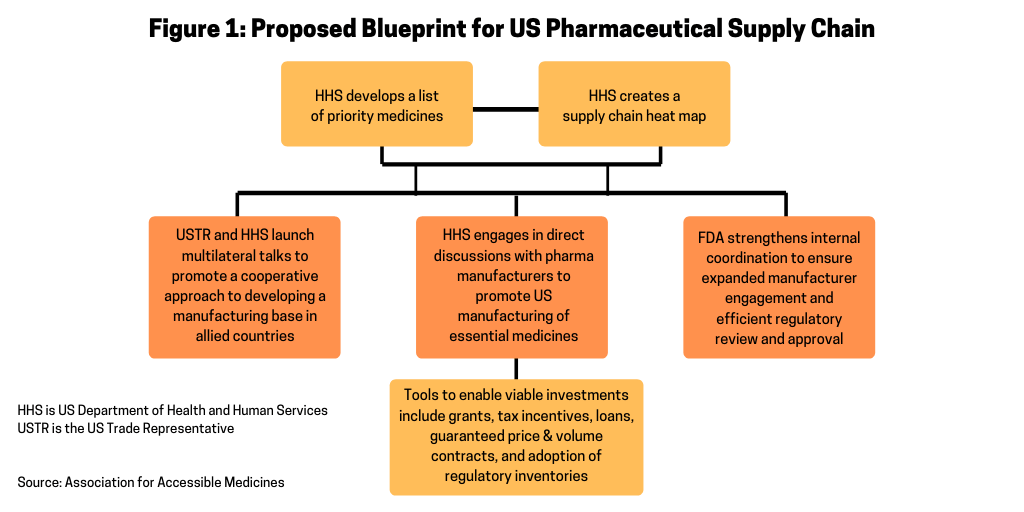

Figure 1 outlines the AAM’s proposal for a way to increase US-based manufacturing by providing the Secretary of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) with additional authority to secure the US pharmaceutical supply chain. The plan involves the HHS Secretary establishing a list of priority medicines and creating a supply-chain map for those medicines. Working with the Office of the US Trade Representative (USTR), which is the government agency responsible for developing and recommending US trade policy to the President of the US, the HHS and USTR would launch multilateral talks to promote a cooperative approach to developing a manufacturing base in allied countries. The HHS would then engage in direct discussions with pharmaceutical manufacturers to promote US manufacturing of essential medicines. The US government would use various tools, such as grants, tax incentives, loans, guaranteed price & volume contracts, and adoption of regulatory efficiencies to encourage onshoring of pharmaceutical manufacturing to the US. Such incentives are considered necessary to offset the cost and time required to build up US-based manufacturing and takes into account certain projections that new manufacturing facilities can cost as much as $1 billion and take five to seven years to build. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) would then strengthen its internal coordination to ensure expanded manufacturer engagement and efficient regulatory review and approval for an expansion or establishment of US-based manufacturing facilities.

List of essential medicines and assessment of the supply chain

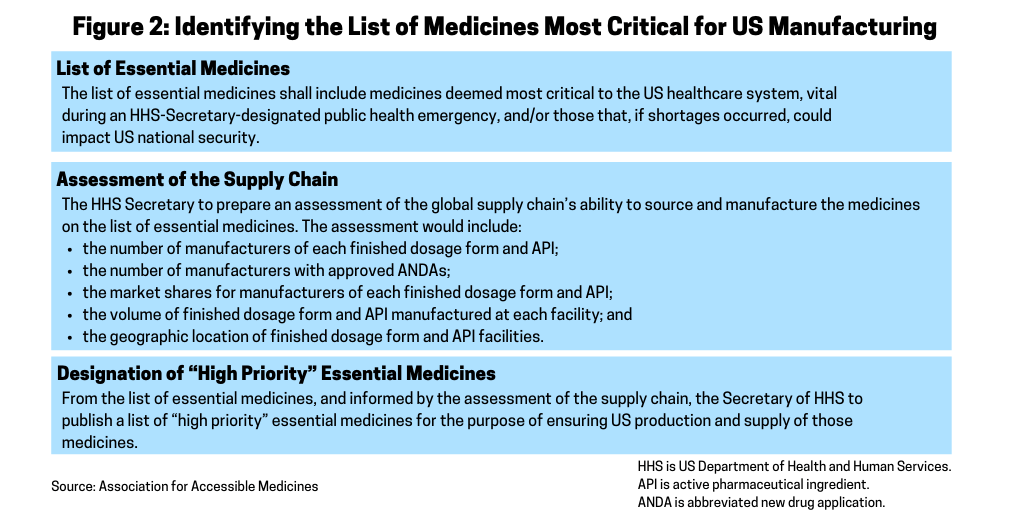

A key part of the AAM’s blueprint for securing the US pharmaceutical supply chain is to provide the HHS Secretary the authority to establish a list of essential medicines for the US (see Figure 2). The AAM recommends that within 180 days of the enactment of the blueprint, the HHS Secretary would establish a list of essential medicines for the US. Essential medicines are defined as the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) and finished dosage form. The list of essential medicines includes medicines deemed most critical to the US healthcare system during an HHS Secretary-designated public health emergency and/or those that, if shortages occurred, could impact US national security. In developing the list, the AAM suggests that the HHS Secretary consult with the FDA, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and other public-health agencies as well as the Secretary of Defense and Secretary of State. The list of essential medicines would be subject to a 60-day public comment period.

Assessment of the supply chain. Within one year of enactment of the blueprint, the AAM recommends that the Secretary of HHS prepare an assessment of the global supply chain’s ability to source and manufacture the medicines on the list of essential medicines (see Figure 2).

Designation of “high-priority” essential medicines. From the list of essential medicines, and informed by the assessment of the supply chain, the HHS would publish a list of “high-priority” essential medicines for the purpose of ensuring US production and supply of those medicines. Publication would occur within two years of enactment of the blueprint. The HHS Secretary would update the list annually and may designate additional medicines, including those not previously deemed essential, as “high priority” during an HHS Secretary-designated public health emergency, according to the AAM’s proposal. The list, and any updates, would be subject to a 30-day public comment period.

Incentives for securing the US pharma supply chain

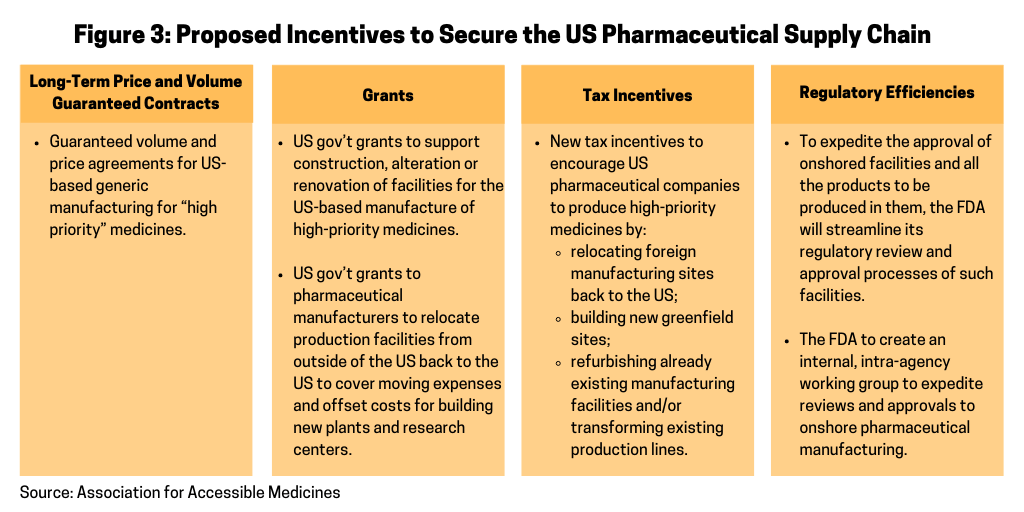

In its blueprint, the AAM outlines several incentives as a means to encourage pharmaceutical manufacturers to repatriate pharmaceutical manufacturing to the US and ways to offset the costs for doing so (see Figure 3). The AAM’s proposal specifies that within six months of the completion of the list of “high priority” medicines, the HHS, acting through the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response under the HHS, would seek new and specific proposals from pharmaceutical manufacturers to determine how individual companies can help secure the US pharmaceutical manufacturing base for priority medicines. Proposals would include the list of specific finished dosage forms and APIs the company proposes manufacturing in the US and the specific type of incentives necessary to make the facilities economically viable. HHS would be authorized to make such incentives available as described in Figure 3 and outlined below.

Long-term price and volume-guaranteed contracts. In its proposal, the AAM says that guaranteed volume and price agreements are essential to ensuring the viability of US-based generic manufacturing for “high priority medicines and to inoculate those investments against low-priced imports of the same medicine from, for example, China.” When engaging with the industry, however, the AAM stresses that the HHS must encourage multiple suppliers in the market and ensure, whenever possible, that no one company supplies the entire market to protect against supply disruptions. The price and volume agreements would provide purchase guarantees that could be spread across the Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) and all federal agencies that procure medicines through the Federal Supply Schedule. For the SNS, the HHS may take possession of such purchases or may pay manufacturers an inventory-management fee to produce and maintain the specified quantity on behalf of the SNS. Specific volume and price levels would be negotiated on a company-by-company basis.

Grants. The AAM’s proposal also calls for the HHS to provide grants to support construction, alteration or renovation of facilities for the US-based manufacture of medicines included on the high-priority medicines list (see Figure 2). Grants would also be provided to pharmaceutical manufacturers to relocate production facilities from outside of the US back to the US to cover expenses in moving production and include funds to offset the cost of building new factories and research centers. Such grants would be available only to manufacturers with an approved abbreviated new drug application (or, in the case of an authorized generic drug, a license to manufacture the drug under another manufacturer’s new drug application).

Figure 3 outlines further incentives that the US government would be able to provide to encourage pharmaceutical manufacturers to onshore pharmaceutical manufacturing back to the US, including tax incentives and ways to increase regulatory efficiency for approving new manufacturing facilities producing high-priority medicines in the US.

While long-term pricing and volume guarantees and grants would be worked out on an individual company basis, there ae several incentives that the AAM recommends could be adopted for the entirety of the US generics or biosimilars pharmaceutical manufacturing base, which would include tax incentives and regulatory efficiencies from the FDA.

Under the AAM’s proposal, new tax incentives would be used to encourage pharmaceutical companies to relocate foreign manufacturing sites back to the US, build new greenfield sites, refurbish already existing manufacturing facilities, and/or transform existing production lines to focus on pharmaceuticals that appear on the HHS’ list of “high-priority” medicines.

Specific recommendations offered by the AAM would allow for a tax deduction during whichever of the two periods is longer: throughout the period the medicine is deemed “high priority” or during the initial period that the company has agreed with the HHS to supply from its expanded investment. Specific tax incentives proposed by the AAM that will facilitate the onshoring of US pharmaceutical manufacturing include: (1) a dollar-for-dollar credit against federal taxes to pharmaceutical manufacturers for 50% of wages, investments, and purchases made for manufacturing medications on the priority medicines list in the US; (2) a tax reduction modeled after the Domestic Production Activities Deduction (Section 199), which provides a tax deduction of as much as 9% of the company’s income attributable to US manufacturing operations; (3) an increase to the R&D credit rate to 20% for the alternative simplified credit; and (4) full expensing for the construction of new factories built to move production from overseas to the US.

To expedite the approval of a facility and all the products to be produced in it, the AAM proposes that the FDA streamline its regulatory review and approval processes by removing duplicated actions and reducing the time for approvals. Under the AAM proposal, the FDA would expand cooperation with the manufacturer by working collaboratively to evaluate and approve the facility and the technology-transfer processes concurrently as opposed to waiting until after the facility is built and the equipment is installed and validated.

To accomplish these goals, the AAM proposes that the FDA create an internal, intra-agency working group focused on helping to expedite reviews and approvals to onshore pharmaceutical manufacturing. This working group would consist of resources from the Office of Regulatory Affairs (inspections); the Office of Pharmaceutical Quality (facilities); reviewers from both chemistry and microbiology disciplines; and the Office of Generic Drugs (overall project management). This working group would be dedicated to the transfer of products back into either US approved facilities or newly constructed facilities at new or existing sites. This working group would grant meetings with the company to discuss the overall transfer plans.

Separately, to promote international cooperation, the AAM proposes that the USTR, working with the HHS, should negotiate a plurilateral agreement with US allies to promote a cooperative approach to securing the US supply chain.