The UK and the Pharma Industry in a Post-Brexit World

The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry, which represents innovator pharma companies in the UK, has put forth its priorities in the UK’s upcoming negotiations on its future relationship with the EU as well as a basis for a free-trade agreement with the US. What is it seeking?

Brexit and the UK pharmaceutical industry

After a multi-year process to exit the European Union (EU), the UK officially exited the EU on January 31, 2020 and entered into a 11-month transition period until the end of 2020 to work out its future relationship with the EU. During the transition period, EU law and rules are still applicable across the UK, and the UK government can prepare trade deals with other nations. Formal negotiations between the UK and the EU to decide the UK’s future relationship with the EU began earlier this month (March 2020) with a second slate of talks scheduled for next week (March 18, 2020). In advance of these talks, last month (February 2020), UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson put forth the UK’s approach for its negotiations on its future relationship with the EU.

“We are seeking the type of agreement which the EU has already concluded in recent years with Canada and other friendly countries,” said Johnson in a February 27, 2020 statement. “Our proposal draws on previous EU agreements such as the Comprehensive Economic Trade Agreement, the EU/Japan Economic Partnership Agreement and the EU/South Korea Free Trade Agreement. And it is consistent with the Political Declaration agreed last October, in which both sides set the aim of concluding a ‘zero tariffs, zero quotas’ Free Trade Agreement,” he said.

“Our approach is based on friendly cooperation between sovereign equals. Our offer outlined today [February 27, 2020] represents our clear and unwavering view that the UK will always have control of its own laws, political life and rules,” said Johnson. “Instead, both parties will respect each other’s legal autonomy and the right to manage its own borders, immigration policy and taxes.”

In response to the UK putting forth its framework for an agreement with the EU, the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI), which represents research-based innovative pharmaceutical companies responded. “The Government has set out a vision for a future relationship where both sides can work together in the interest of patient safety, public health, and the pursuit of scientific progress for UK and EU citizens,” said Richard Torbett, ABPI’s Chief Executive in a February 27, 2020 statement. “As negotiations get underway, we urge ambition and pragmatism to achieve these goals.”

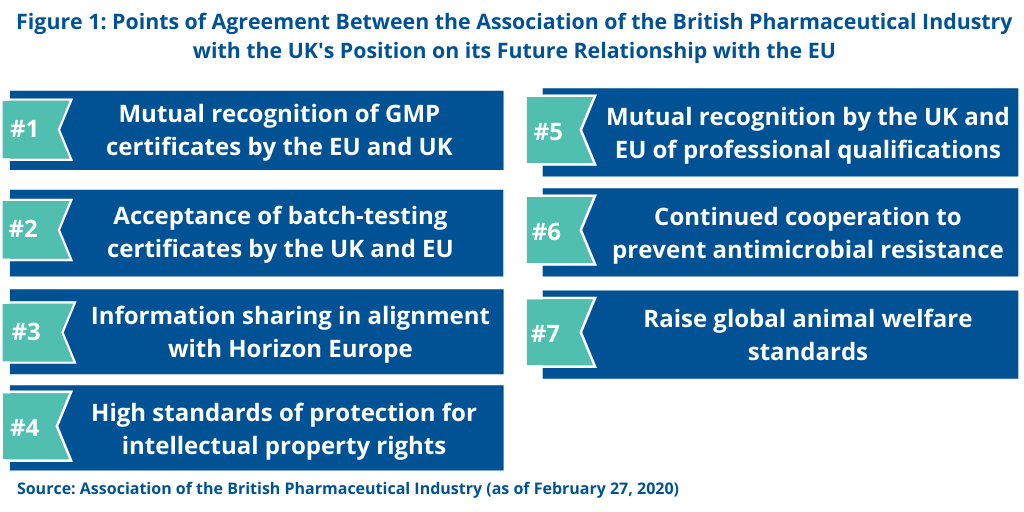

The ABPI specified several goals of the UK government in which the UK pharmaceutical industry supports (see Figure 1). First is an annex of medicinal products that support mutual recognition of GMP certificates and acceptance of batch-testing certificates by the regulatory authorities of the UK and EU. The ABPI is also supporting information sharing, so that regulators can safeguard patient safety and public health.

Additionally, the ABPI supports the UK government’s position for participation in Horizon Europe. Horizon Europe is an EUR 100 billion ($113 billon) research and innovation program funded by the European Commission over seven year (2021-2027) to succeed Horizon 2020, the current EU research and innovation program with nearly EUR 80 billion ($91 billion) of funding available over seven years (2014 to 2020). In setting forth the missions or focus areas of Horizon Europe, cancer research is one targeted area. The other focus areas are: adaptation to climate change, including societal transformation; healthy oceans, seas, coastal and inland waters; climate-neutral and smart cites; and soil health and food.

The ABPI is further supporting high standards for the protection of intellectual property rights as well as mutual recognition of professional qualifications. Additionally, the ABPI supports the UK’s goals to have continued cooperation to prevent antimicrobial resistance and to raise global animal welfare standards.

Pharma and a UK–US free-trade agreement

As the UK readies itself in negotiations with the EU, it is also open to negotiate free-trade agreements with other countries, including the US. Earlier this month (March 2020), the UK government, through the UK Department of International Trade, put forth its objectives for a free-trade agreement with the US as talks are expected to begin this month (March 2020). The importance of the US to the UK as a trade partner is clear. In 2019, UK-US total trade (goods and services) was valued at £220.9 billion ($286 billion), which includes 19.8% of all the UK’s exports. The UK government’s analysis shows a UK–US free trade agreement could increase trade between both countries by £15.3 billion ($19.8 billion) in the long run. The US currently levies £451 million ($584 million) in tariffs on UK exports each year.

On the UK side, talks for a UK–US free-trade agreement will be overseen by Crawford Falconer, the UK Department of International Trade’s Chief Trade Negotiation Adviser, and formerly New Zealand’s Chief Negotiator and Ambassador to the World Trade Organization. Negotiating rounds will alternate between the UK and US. The UK government says it will set out its negotiating objectives for Australia, Japan and New Zealand shortly, with the aim of having 80% of total UK external trade covered by free-trade agreements by 2022.

The UK’s International Trade Secretary, Elizabeth Truss, and the US Trade Representative, Robert Lighthizer, met in London late last month (February 2020) to reiterate their commitment to get on with negotiating a free-trade agreement and improving the bilateral trading relationship between the US and the UK. Lighthizer, along with the US International Trade Secretary, Liam Fox, are jointly chairing the US-UK Trade and Investment Working Group, which was formed in 2017 to provide commercial continuity for US and UK businesses as the UK leaves the EU and to lay the groundwork for a potential, future free-trade agreement once the UK left the EU.

Following the release of the UK government’s framework for a free-trade agreement with the US, the UK pharmaceutical industry, through the ABPI, provided support for moving along on such an agreement.

“The US and the UK are two of the most advanced economies in the world and are home to thriving pharmaceutical sectors,” said the Chief Executive of the ABPI, Richard Torbett, in a March 2, 2020 statement. “This FTA [free-trade agreement] is an opportunity to build on those mutual strengths and remove trade barriers. This negotiation will set the tone for the UK’s future trade agenda: one which should support Britain’s world-leading science.”

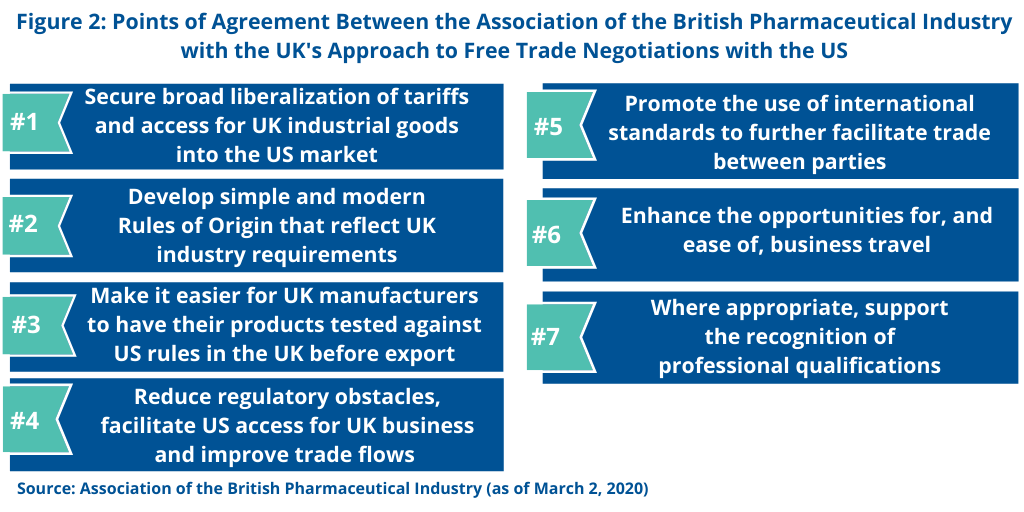

The ABPI says that the UK objectives contain specific areas that the pharmaceutical industry supports (see Figure 2). These involve broader business and regulatory objectives that are part of the UK’s negotiating framework.

Liberalization of tariffs. The ABPI supports the UK’s interest in securing liberalization of tariffs and access for UK industrial goods into the US market. Trade in goods between the US and the UK was £104.4 billion ($134.4 billion) in 2019, and the UK says it supports a further liberalization of tariffs in certain sectors, including chemicals and industrially manufactured products. In a UK–US free-trade agreement, the UK says it will seek to reduce or remove tariffs for UK exports, thereby making them more competitive in the US market. Similarly, the US has indicated its intention to seek to reduce or remove UK tariffs on US exports in a free-trade agreement. The UK government said it would be mindful to strike the appropriate balance so that the lower cost of US-based goods does not adversely compete with UK-based goods.

Rules of origin. The ABPI also supports the UK’s position that rules of origin should be simple and modern and reflect UK industry requirements in a free-trade agreement with the US. Rules of origin are a key component of any trade agreement as they define what goods can benefit from the liberalization achieved in the agreement. They also ensure that only goods from countries that are party to the agreement benefit from lowered tariffs by preventing circumvention.

“We will seek simple and modern rules that facilitate trade between the UK and US while also addressing any unfair and unreasonable practices to circumvent tariffs or quotas,” said the UK in the report of the UK Department of International Trade that set forth the UK’s negotiating framework for a free-trade agreement with the US. “Equally, we will reflect UK industry requirements and consider existing (as well as opportunities for future) supply chains.”

Product testing. The ABPI also supports the UK’s position that a free-trade agreement with the US should make it easier for UK manufacturers to have their products tested against US rules in the UK before export.

Reduce regulatory barriers. The ABPI also supports the UK’s position in a free-trade agreement with the US to reduce regulatory obstacles, facilitate US access for UK business and improve trade flows through good regulatory practice and regulatory cooperation. The UK government says that a transparent, predictable, and stable regulatory framework provides confidence and stability to UK exporting businesses and investors. The UK government says it will also seek to secure commitments to key provisions such as public consultation, use of regulatory impact assessment, retrospective review, and transparency, as well as regulatory cooperation.

International standards, facilitation of business travel, and professional qualifications. The ABPI also says it supports the UK’s position in negotiating a UK–US free-trade agreement that such an agreement would promote the use of international standards to further facilitate trade between parties. The ABPI also supports the UK’s interest in a free-trade agreement with the US to enhance the opportunities for, and ease of, business travel and, where appropriate, supporting the recognition of professional qualifications.

Not on the negotiating table: drug pricing

One area that is specifically not on the negotiation table, according to the UK government, is drug pricing, which is administered through the National Health Service (NHS), the publicly funded healthcare system in the UK. “The NHS will not be on the table,” said the UK Department of International Trade in its report. “The price the NHS pays for drugs will not be on the table. The services the NHS provides will not be on the table. The NHS is not, and never will be, for sale to the private sector, whether overseas or domestic. Any agreement will ensure high standards and protections for consumers and workers, and will not compromise on our high environmental protection, animal welfare and food standards.”

UK’s position on intellectual property protection of pharmaceuticals

With respect to pharmaceuticals, the UK also recognized concerns raised by some on how to balance incentives for innovation through patent protection and affordability and access to medicines. The UK held a public consultation period from July 2019 to October 2019 and in the report of the UK Department of International Trade, the UK government responded to that feedback.

“There was concern about how we strike the right balance in the level of IP [intellectual property] protections, particularly in the areas of pharmaceuticals and patents,” said the UK Department of International Trade in its report. “The Government recognizes that an effective global IP system needs to strike a balance between supporting research and innovation through the incentives created by the patent system and reflecting wider public interests such as the dissemination and affordability of medicines. In negotiating the UK–US FTA [UK–US free-trade agreement] we are committed to maintaining this balance.”

The UK government added that the UK and US are already committed to the international Doha Declaration, which refers to several aspects of TRIPS (Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) under the World Trade Organization (WTO). The Doha Declaration allows the world’s least developed countries, who are members of the WTO, to remain exempt from patents on pharmaceuticals until 2033 if they so wish. The UK says it will continue to support the Doha Declaration.

In seeking public consultation on its negotiating position for a UK-US free-trade agreement, some non-governmental organizations argued that wider medical patent protections, beyond the WTO TRIPS provisions, affect access to generic or affordable medicines in the UK.

Respondents also raised concerns around the future compatibility with international obligations the UK is already party to, such as the European Patent Convention (EPC). “The Government recognizes the importance of the UK continuing to be party to the EPC,” said the UK in its report. “The Government notes that there are clear benefits for countries seeking a trade agreement with the UK to have access to patent protection in the UK and other EPC parties through the European Patent Organization (EPO).”

Future relationship with the EMA

The UK also noted from its public consultation that pharmaceutical industry association respondents said that continued alignment with standards and regulations used in the EU, including future cooperation with the European Medicines Agency, was flagged as a top priority.